[click images for larger versions]

You know how sometimes when you first come across a new topic or thing and you see it from one particular angle that makes you like it so you retain a sympathetic viewpoint as you rummage around for more information?

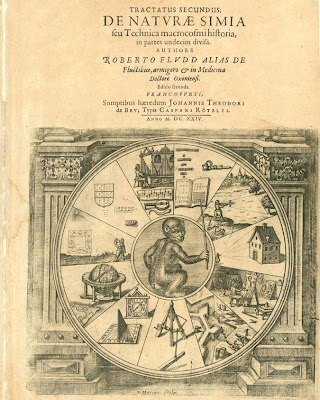

That's how I felt about the enigmatic and controversial Robert Fludd (1574-1637) as I made my way through his 'De Naturae Simia' book from the enormous 'Utriusque Cosmi Maioris Scilicet et Minores Metaphysica, Physica Atque Technica Historia' series, published by Theodore de Bry in batches between 1617 and 1626, online at the J Willard Marriot Library at the University of Utah.

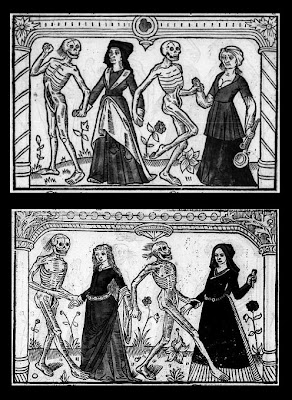

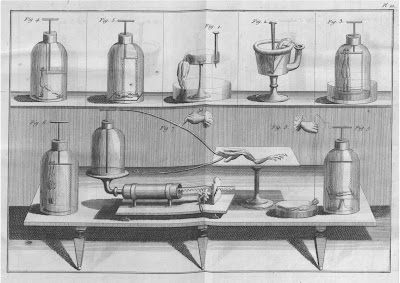

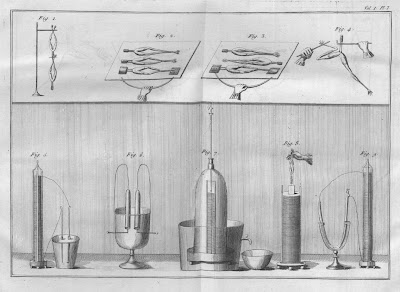

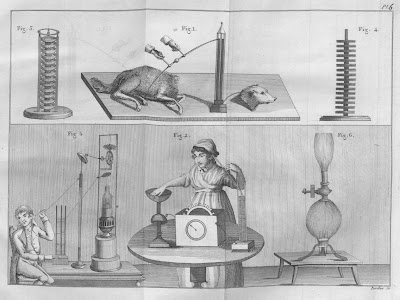

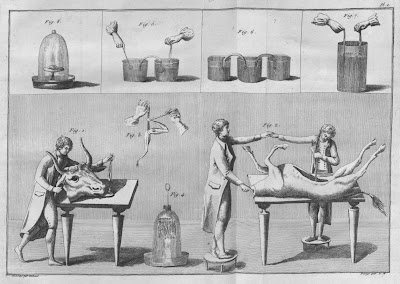

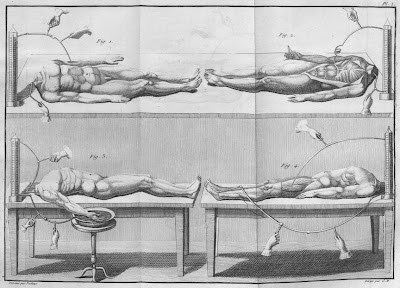

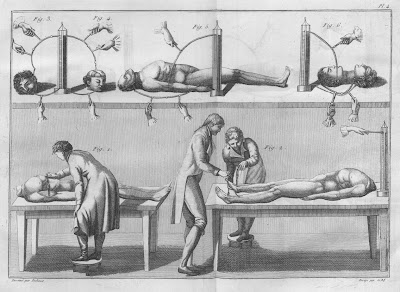

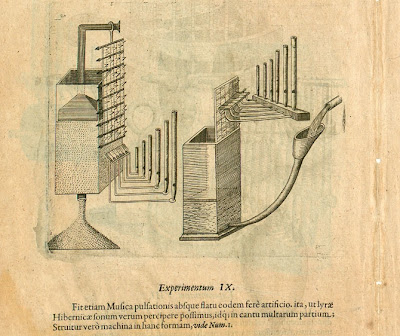

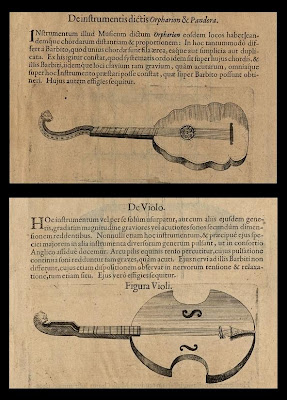

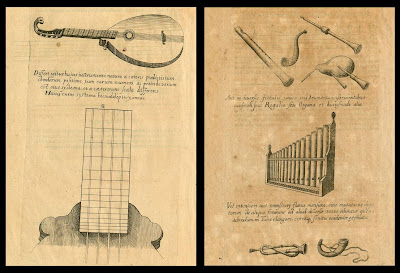

Paging through the website's edited but extensive selection of Fludd's work, it was easy to develop admiration and respect for this polymath who was attempting to document the logical world. He sets down theories and descriptions in latin (all extensively illustrated) covering mathematics, geometry, music, artistic and architectural perspective, horology, military fortifications, astronomy, engineering machines and no doubt other subjects I'm forgetting. Some of the ideas are of course fanciful or perplexing at best, but overall there's this sense that Fludd had an orderly and enquiring scientific mind.

History doesn't have such a singularly supportive view of our man Fludd. After completing his medical studies, he toured the continent for 6 years during which time Fludd became interested in alchemy and Rosicrucianism. From then on his views and extensive publications present a mystical, hermetic philosophy as Fludd attempted to incorporate the ideas of Paracelcus into an essentially staunch religious framework. His medical practice involved a fair sampling of astrology and faith healing and Fludd's forceful and magnetic personality was said to help cure his patients.

Fludd was accused of being a magician and a heretic and even the astronomer Johannes Kepler was moved to publish criticisms of the hermetic approach to knowledge. Much of the prolific output of Fludd was devoted to defending the cosmic harmony proposed by alchemists and the Rosicrucian movement. While on the one hand he may come across as a champion of the esoteric sciences, Fludd was also the first to support Harvey's theory about the circulation of blood, he believed in a heliocentric universe, was thought by some to have invented the barometer, obtained a patent from the Privy Council for making steel and he still had time to be a Censor for the Royal College of Physicians.

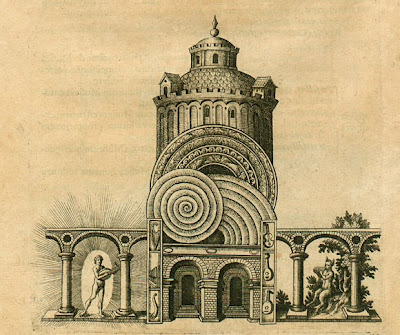

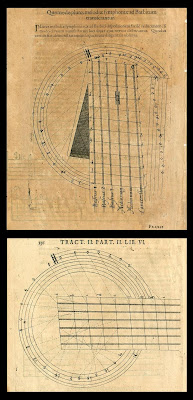

That initial positive reaction I felt leafing through 'De Naturae Simia' was due in no small part to the sections devoted to music. I can't read latin almost at all and I have no academic knowledge in relation to music or music history, but there is a distinctly studious feeling attached to the musical maps and musical notation illustrations (many done by Matthäus Merian), beyond the allegorical fancy of the Temple(s) of Music. Perhaps it's naive on my part but I couldn't help thinking that this was an intellect worth exploring.

Virtually all the above images were uploaded at full size. A few have been touched up - which ones? One or two of the illustrations are borderline non-musical and in fact, that last image, with the 4 illustrations, are mathematical calculation maps. I've got a whole load more images for a second post in a day or 2 and it was a toss up how to divide them between entries. If you want to find any of the above images in the cumbersome Utah University website, the page numbers are all listed in the image alt-tags (right click the image & choose 'properties').

- The complete 'Utriusque Cosmi Maioris Scilicet..' (grey scale illustrations) is actually available as multiple zip files or as an enormous pdf for download.

- Biographies: NNDB; Galileo Project; Wikipedia; Fludd chronology.

- At Levity, about halfway down the page, is an interesting exchange about the allegorical nature of our simian friend on the titlepage above.

- 'Robert Fludd: A Picture in Need of Expansion' © Ron Heisler.

- Doctor Robert Flood by Sharon MW, also at Levity.

- 'Robert Flood and the End of the Renaissance' (W. Huffman 1988) - book review by John Henry.

- The last alchemist.

- Images at JR Ritman Library, Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica.

- First page from a subscription only article on the musical instruments in Fludd's books.

- Pink Floyd ?!

- See also: Part II, Fludd Returns.